Principal component analysis.

Principal component analysis is a statistical dimensionality reduction technique that transforms correlated variables into independent orthogonal components. Its purpose is to simplify complex data structures by maximizing explained variance and eliminating informational redundancy through methods such as singular value decomposition.

If you’ve seen Interstellar, the Christopher Nolan movie, you surely remember that peak moment where Cooper goes into a black hole and ends up floating in a tesseract behind his daughter’s bookshelf. There he is, trying to communicate complex quantum data about gravity through a wristwatch, using something as rudimentary as Morse code. It is the perfect definition of frustration: you have an immense, complex reality full of strange dimensions, but you only have a limited channel to explain it without poor Murph’s head exploding. How do you compress the complexity of the universe into the ticking of a watch’s second hand?

That sci-fi drama is, ironically, the bread and butter of data analysis. We live bombarded by variables: age, weight, height, cholesterol level, Instagram likes, hours of sleep… If we try to analyze it all at once, we end up like Cooper: screaming into the void while the rest of the world looks at us funny. Sometimes, so many variables just add noise, repeating the same thing with different words. We need a way to simplify, to find the gravitational force that unites those scattered data points and project them into a reality we can paint on a sheet of paper (or a bookshelf, for that matter).

This is where statisticians, who are the true space-time travelers, albeit with a lower budget for special effects, whip out their tool for the occasion: principal component analysis (PCA). Just as the tesseract simplified dimensions so Cooper could return from the black hole, PCA takes the chaos of multidimensional data and flattens it, keeping only what matters most: variance.

Get ready, because in this post, we’re going to reduce dimensions without needing to get anywhere near a gravitational singularity like Gargantua.

Principal component analysis: the obsession with the perfect shadow

To understand how PCA works, you need to drop the calculator and fire up your imagination. Visualize a giant rubber duck. Yes, one of those neon yellow ones Godzilla would use if he decided to take a bubble bath. Imagine you have this majestic three-dimensional object floating in the air, and your mission is to explain to Flatty, a fictional two-dimensional being (basically, a piece of paper with legs) who has never seen volume, what a rubber duck is. Your only tool is a spotlight to project the duck’s shadow onto the wall.

If you are a terrible photographer and point the light directly down at the top of the duck’s head, the shadow you’ll project will be… a shapeless oval. You will have reduced the dimensions (from 3D to 2D), yes, but you’ll have destroyed the vital information: Flatty will think a duck is just a mustard stain or a rotten potato. You’ve chosen a projection with very little information and zero distinction.

However, if you put in a little effort and rotate the duck until it’s perfectly lit from the side, the shadow will reveal that unmistakable silhouette with its beak, its perky tail, and that smug little smile rubber ducks always have. That is the “best shadow”, the one that preserves the essence and dignity of the original duck while reducing its dimension from our three-dimensional world to Flatty’s two-dimensional one.

Well, PCA is nothing more than an obsessive mathematical photographer dedicated to rotating the data until finding the exact angle where the projected shadow is as large, sharp, and detailed as possible, preventing the duck from looking like a potato.

Navigating by intuition

Now that we’ve understood that we are looking for the best possible shadow to avoid making fools of ourselves, let’s descend from the abstraction of bath toys to the reality of data to try and see, graphically, how PCA works.

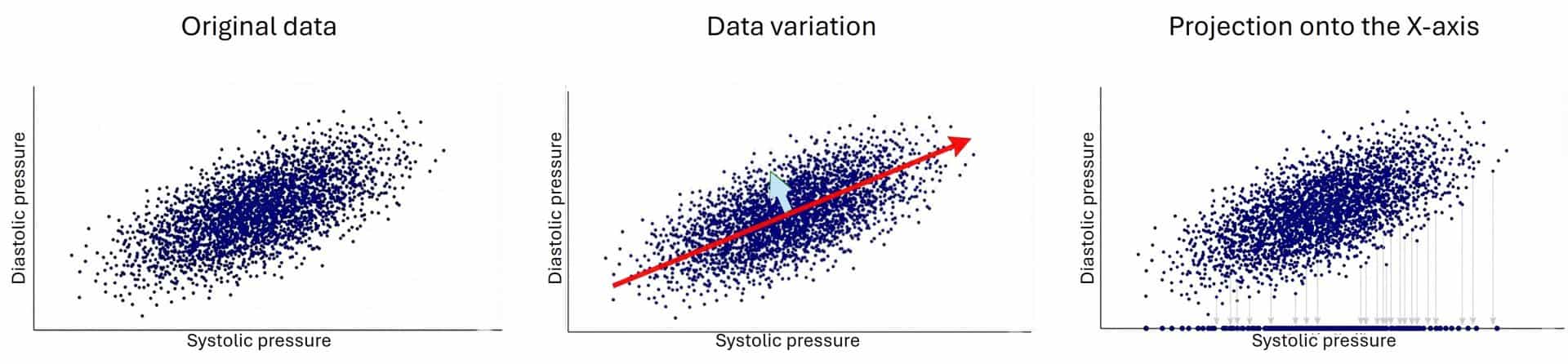

Imagine we have health data for a thousand astronauts, including their systolic and diastolic blood pressure. If we plot this data on a graph, we’ll see that the points aren’t scattered at random; instead, they form a sort of elongated cloud. This happens because both variables are correlated: if your high pressure goes up, your low pressure usually follows.

You can see this in the attached figure. The values vary in two directions. The most important one is the upward trend followed by the cloud of points, moving up and to the right. However, if you look closely, they also vary in a second direction, perpendicular to the first (orthogonal, to use the fancy term), which gives “thickness” to that elongated rugby ball shape formed by the data. I’ve shown this in the graph with two vectors. The red vector (the long one) represents the general trend: the strong relationship between both pressures. The blue vector (the short one) represents the remaining variability, the small individual deviations from that general rule.

Now, let’s think about how we could simplify this data. Suppose we want to reduce them to a single dimension instead of the two they currently have (it goes without saying that, in real life, we wouldn’t do such a thing with such simple data, but it’s for the sake of representation and understanding).

If we try to simplify by projecting all the points onto the original horizontal axis (X-axis, systolic) or the vertical one (Y-axis, diastolic), we will lose valuable information. Why? Imagine crushing that rugby ball against the wall of the X-axis. By doing so, you ignore the contribution of the other variable. Worse still, if there were different groups of astronauts (say, three different clinical clusters), by blindly projecting them onto an original axis, these groups could overlap and blend, making it impossible to tell them apart. We would be mixing different populations and losing the true structure of the data, just like when we lit the rubber duck from above.

Whenever we simplify, we lose some information, but we must strive not to lose the actual structure. This is where PCA proposes something smarter. Instead of resigning ourselves to the axes that come with the original data, we are going to rotate the coordinate system to see what we can achieve.

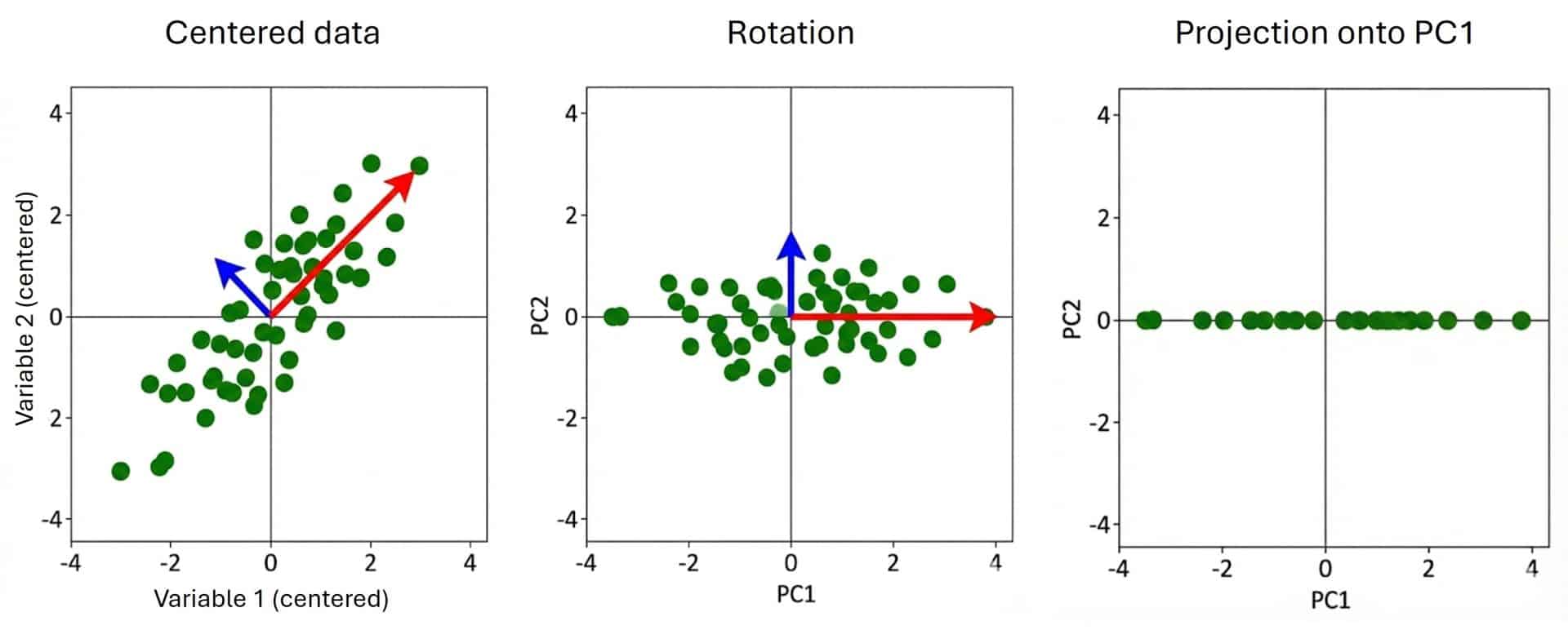

First, we center the data by subtracting the mean from each point, moving the cloud so its center is at the origin (0,0). Once centered, we look for a new direction (the red arrow) that pierces the cloud of points exactly through its longest part. Mathematically, we are looking for the line where, if we project the points, they stay as far apart as possible. That direction captures the greatest amount of the variance in the data.

Finally, we rotate everything so that the red arrow becomes our new X-axis, which we shall pompously christen as the first principal component (PC1). Notice the magic here: this PC1 is neither the high pressure nor the low pressure, but a linear combination of both that captures the “essence” of overall blood pressure.

Then, we look for a second direction that must follow a golden rule: it has to be perpendicular to the first. That is the blue arrow. This direction explains “what’s left”, that residual variance that gives the rugby ball its width. That will be our second principal component (PC2).

In the end, what we are doing is rotating the “camera” through which we view the data. We move from seeing them from the “systolic vs. diastolic” angle to seeing them from the “general blood pressure (PC1) vs. specific deviation (PC2)” angle. And since PC1 is so good at summarizing the story, we can often afford the luxury of discarding PC2, having lost very little information in the process.

Cooper cracks the numbers

Now we are going to translate what we’ve understood graphically into numbers. After all, Cooper didn’t dive into a black hole for us to get cold feet now over a couple of additions and subtractions.

We are going to analyze a completely fictional example, but one that could be vital for the survival of the Endurance mission: the suitability of candidate planets.

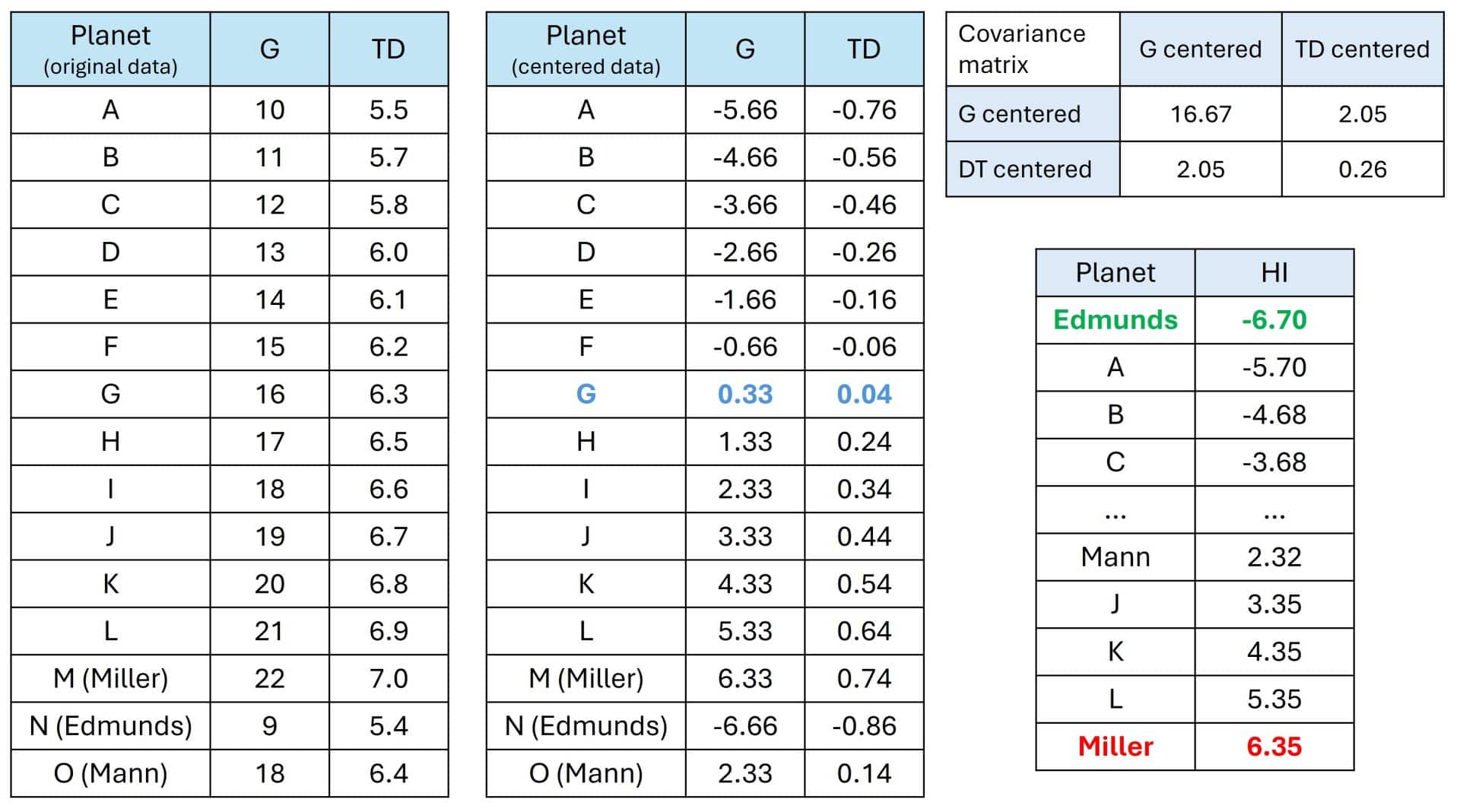

Let’s take a bit of poetic license and imagine that TARS (that clever robot) has scanned 15 potential planets and given us two key data points to know if humanity can live there or if we’ll be crushed in five minutes. You can see the data in the attached table, showing gravity (G) in m/s2, and time dilation (TD), how many years pass on Earth for every hour spent on the planet (yes, the famous “one hour here is seven years there”).

If you look at the table below, you’ll see a clear, yet terrifying, trend: planets with higher gravity tend to be closer to Gargantua, meaning they have more extreme time dilation. There is a positive correlation… and a dangerous one for Cooper and his crew.

For instance, Miller’s planet (M) has a crushing gravity of 22 (remember Earth’s is 9.8) and a dilation of 7 years per hour. Pure hell. On the other end, Edmunds’ planet (N) is much friendlier. Cooper is interested in calculating a parameter that helps him weigh both data points to easily choose which one is most compatible with the mission’s success.

So, he decides to use PCA, which will help him summarize these two columns into a single number that, in a bold display of creativity, he names the hostility index (HI).

The first thing he does is take the entire cloud of planetary data and move it so the center is at the origin of the coordinates. He calculates the mean for G (15.67) and the mean for TD (6.26) and subtracts them from each planet’s values. You can see the whole numerical process in the tables.

Now, negative values mean planets that are “safer than average,” and positive values are “death traps.” Planet G is the middle ground, neither here nor there. If it has breathable air, it might be ideal, provided it doesn’t smell like sweaty socks.

The second step is calculating the covariance matrix, our space-time fabric. Basically, it’s a table TARS spits out to tell Cooper how the variables relate. On the main diagonal, we see the variances, which tell us that gravity (16.67) varies much more in our data than time dilation (0.26). The rest of the numbers are the covariances between the two variables. Since it’s positive (2.05), it confirms that the higher the gravity, the more time Murph will lose waiting for her father to return.

This is the point where Cooper starts to sweat a little: his instruction manual says he has to calculate the eigenvalues and eigenvectors.

To keep your head from exploding with algebra, remember the arrows from the first graphs I showed you. Well, the eigenvectors are, literally, the directions they point in (the red arrow crossing the cloud lengthwise and the blue arrow widthwise). On the other hand, eigenvalues are simply the numbers that tell us the “strength” or length of those arrows, that is, how much information they capture. The red arrow (PC1) has a large eigenvalue (because it explains almost all the variance), while the blue arrow (PC2) has a tiny one, as it barely covers any distance or adds anything new.

The ship’s computer runs the numbers and finds that PC1 has an eigenvalue of 16.92 (huge) and an eigenvector with coordinates (0.99, 0.12). This component points almost entirely in the direction of gravity but drags time dilation along with it. If we look at PC2, its eigenvalue is 0.004 (insignificant stardust) and its eigenvector points toward (0.12, -0.99).

How do we interpret this? Imagine all the information we have about the planets is a pie. The total size of that pie (total variance) is the sum of all eigenvalues (16.92 + 0.004). If we want to know how much of the pie our first principal component eats, we just divide its share by the total:

Variance explained by PC1 = 16.92 / (16.92 + 0.004) = 0.9997

A striking result. In percentage terms, 99.97% of the information about the planet’s hostility is captured in the first component. The second component is just 0.03% noise, totally irrelevant for deciding where to land.

Now, Cooper only has one decision left: which planet to land on? But first, TARS has to convert those pairs of data (G and TD) into a single final score. How does he do it?

Here we witness the magic of PCA again. It doesn’t just project the points with a laser cannon onto the new direction; it creates a new mathematical model, much like a regression equation. PCA builds a formula to calculate our hostility index (PC1) by mixing the two original variables according to the importance given by their eigenvectors.

Thus, we multiply the (centered) gravity by 0.99, multiply the (centered) time dilation by 0.12, add both results, and… voilà! We have the HI.

For example, look at the terrifying Miller’s planet: it had a centered gravity of 6.33 and a centered time dilation of 0.74. Applying the formula: HI = 6.35.

By applying this formula to all planets, we have simplified the universe. In the final table, you can see the definitive hostility ranking calculated by TARS.

What have we achieved? Instead of looking at two variables and arguing over whether gravity is worse than missing your children’s childhood, we now have a single, mathematically calculated number, PC1, that summarizes the “harshness of the planet.” Miller’s planet gets a 6.35 (pure danger). Edmunds’ planet gets a -6.70 (the new home).

That is what PCA does: it compresses the complexity of the universe into something that fits in a Morse code message through a watch. Murph would be proud.

SVD: the mathematical wormhole

The example we’ve seen so far is ridiculously simple, but if we want to represent it graphically and crunch the numbers by hand, it must be that way. In real life, however, datasets are much larger and involve a much higher number of variables. This is where PCA truly shines: summarizing the variance (or a large part of it) generated by dozens or hundreds of variables into just two or three principal components.

Needless to say, all of this is done using a computer and software, such as R, which can perform all these steps if you choose the “long road” of the covariance matrix, eigenvectors, eigenvalues, and so on. However, there is an even more elegant and computationally efficient shortcut: the singular value decomposition (SVD) method.

The SVD method is numerically more stable and avoids rounding errors because it works directly with the data matrix without needing to calculate the covariance first. The idea is that the centered data matrix (X) can be decomposed into three “magic” matrices:

X = U · D · VT

Don’t let the linear algebra intimidate you. Let’s translate this into simpler language:

VT is the transposed matrix of the eigenvectors. It contains the vectors that tell us where to rotate the map to align our axes with the maximum amount of information. Basically, it tells the data: “Rotate 30 degrees to the right (for example), because that’s where the maximum variance is.”

D is a new element for us: a diagonal matrix containing the famous singular values. These act as a sort of scale factor that determines how much the data is stretched or compressed in those new directions. If the value is large, that direction is a high-speed highway of important information; if it’s small, it’s a goat track (noise) that we can safely ignore.

Finally, the U matrix is the projection map of the data. Once we have rotated and stretched the data, this matrix tells us exactly where each point falls in this new system. These are the final normalized coordinates.

Now we can understand the previous formula. It simply tells us that the original data (X) is the result of taking a position on the map (U), stretching it according to its importance (D), and rotating it so it fits into the reality (VT) of the new principal component.

We’re leaving…

And with that, we’re hopping into the tesseract to exit the brane and take advantage of the fourth dimension to get back home from Gargantua before it gets dark. In other words, we’re wrapping this up.

We’ve seen that, whether it’s avoiding shapeless ducks or choosing a planet that won’t kill us in five minutes, the secret isn’t always about piling up mountains of data. It’s about finding the perfect angle, that sharp shadow that tells the real story while ignoring the background noise. In the end, PCA is nothing more than a mathematical Occam’s razor: if you can explain the universe with one single line, why would you need two?

Hard as it may be to believe after such a long post, we haven’t actually covered even half of what there is to say about PCA. We’ve merely tiptoed around the dense mathematical plumbing so no one would go running for the hills.

For example, we haven’t mentioned the assumptions the data should ideally meet, like that famous “normality” statisticians love to demand for everything, even though PCA is quite a rugged, all-terrain tool. Nor have we discussed the golden rule that keeps the system from cheating: for PCA to work, there’s a mandatory constraint stating that the sum of the squares of the coefficients (the weights we give to each variable) must equal one.

Why? Because if we didn’t set that limit, the math would simply use infinitely large weights to artificially maximize variance and “win the game” without providing any real information. It’s a whole world of scandalous details and theorems capable of causing severe insomnia. But that’s another story…