Central limit theorem.

The central limit theorem states that if we take a sufficiently large number of random samples from the same population and calculate the mean for each sample, the distribution of those means will tend to follow a normal distribution, regardless of the original distribution of the data. This allows for the safe application of many statistical analyses, such as estimating confidence intervals and hypothesis testing.

If we go by the movies, we have more ways to go extinct than recipes for making an omelet: meteors, zombies, pandemics, killer robots, unfriendly aliens, AI with a god complex, and of course, everyone’s favorite: ourselves, slowly ruining everything one bad decision at a time.

They say humans are the smartest species on the planet. They also say crows can recognize human faces and solve puzzles faster than many hungover students. So… who do we trust more? Because honestly, the way things are going, human intelligence feels like it’s on clearance: used up quickly, repeated too often, and rarely comes with instructions. If we do go extinct, it won’t be because of a meteor or a killer virus, it’ll be because someone made a TikTok chugging bleach while arguing on X about whether the Earth is flat.

And here’s the funny part: despite the chaos, the noise, the social media mess, the fake news, and the speeches that sound like last-minute PowerPoints from sleep-deprived interns… there’s still logic behind it all. A numerical logic, hidden, stubborn, and very real. Because no matter how special or enlightened we think we are, in the end, we behave like data. Billions of data points, each with their means, their variances… and most importantly, their standard errors. That tiny margin that reminds us that one observation doesn’t explain the whole picture.

In this post, we’re diving into the central limit theorem, that statistical gem that shows how, out of chaos, order emerges. Even if each individual is a walking mess, when you zoom out, they start to resemble something… maybe even a nice, symmetrical bell curve. And that’s the irony: maybe we won’t survive because we’re smart, but because our mistakes cancel each other out. One person’s blunder balances out another’s stroke of luck. Either that, or the algorithm will be the one to finish us off.

A world full of noise

As individuals, the so-called human beings are hard to figure out. We do weird things, make questionable choices, and sometimes give answers as random as a badly thrown die. So, it’s no surprise that we run into the same kind of chaos in clinical practice: one patient’s fever drops within ten minutes of taking paracetamol, another doesn’t cool down even with ice, and a third swears their grandmother’s soup did the trick.

But something curious happens when we group enough cases together. What looked like noise starts to show patterns, as if individual madness gets smoothed out in the crowd. This is where the central limit theorem comes into play, that concept that sounds like the title of a sci-fi movie, but is actually one of the most solid foundations we have for trusting data, making evidence-based decisions, and supporting many of the statistical methods we use in clinical research.

The central limit theorem

As we’ve already mentioned, the central limit theorem is one of the most powerful and useful tools in all of statistics. In short, it states that if we take a large enough number of random samples from the same population and calculate the mean of each sample, the distribution of those means will tend to follow a normal distribution, regardless of the original distribution of the data.

In other words, even if the individual data points are chaotic, skewed, or extreme, the means of many samples spontaneously arrange themselves into a shiny new Gaussian curve, symmetrical and predictable. If you’ll allow me a bit of poetic license, you could say that normality arises from chaos.

Beyond its inherent beauty, this has huge practical implications. It allows us to work with real-world clinical data, which rarely follows an ideal distribution, and still apply statistical tools that assume normality, what we call parametric techniques. These are more precise and powerful than non-parametric ones, which don’t rely on any assumptions about the data’s distribution.

But don’t get confused: it’s not that the data magically becomes normal. What normalizes is the distribution of the sample means we draw repeatedly from the population, and that’s enough to apply parametric tests, calculate confidence intervals, or make inferences.

Statistics shows us that even when individual cases seem chaotic or unpredictable, a structure emerges when we look at them together: a hidden logic that helps us understand the behaviour of the group as a whole.

A mathematical metamorphosis

The central limit theorem has a sublime mathematical proof, but it’s only within reach for a lucky few, and I’m not one of them. So instead, let’s look at a practical example to back up what I’ve been saying. We’ll see how a skewed, discrete distribution, like the binomial, magically transforms into a majestic bell curve.

Imagine a very simple clinical scenario: a new treatment has just been developed for the dreaded disease fildulastrosis, and it shows a 20% chance of success. That means that, on average, two out of every ten patients treated will respond positively. We’re dealing with a binomial variable: each patient has a fixed probability of success (p = 0.2) and only two possible outcomes: success or failure.

Now suppose we apply the treatment to 1000 independent samples, each with 10 patients, and record how many patients respond in each group. The expected average is 2 successes per group, but the values range from 0 to 10. The resulting distribution is clearly irregular, discrete, with visible peaks, and skewed to the right, just as shown in the figure. The variability is high, and the shape is far from anything resembling a normal distribution.

Now imagine we repeat the experiment with 1000 samples of 30 patients each. The expected mean is now 6 successes per group. This time, the distribution starts to smooth out: most values fall between 4 and 8, the extremes are less common, and the overall shape begins to look symmetrical. Even though we’re still dealing with a discrete variable, the curve starts to resemble a bell.

Finally, we run the test with 1000 samples of 100 patients. The expected mean is now 20 successes. The resulting distribution is nearly indistinguishable from a normal one, symmetrical, seemingly continuous, and with most values clustered between 17 and 23. Even though we’re still counting successes (a binomial variable), the shape has morphed into a smooth curve that closely matches a normal distribution.

So, as we increase the sample size, even binary variables begin to behave like normal ones. This behaviour is exactly what makes so many statistical analyses, like confidence intervals and hypothesis testing, safe to use, even when the original data doesn’t follow a normal distribution.

Don’t trust the mean alone

If we go back to the previous example, by repeating the experiment many times, we get a rough idea of the population parameter, since we can’t measure it directly. So, the mean of those results gives us a point estimate of that elusive, hard-to-reach value.

But the central limit theorem goes a step further. Since our sample means tend to follow a normal distribution, we can also measure how much those means vary, which gives us a sense of how reliable our estimate is.

That measure of variability in the sample means is none other than the standard deviation of the sampling distribution, arguably the most well-known measure of spread. But in this specific context, it goes by a different name: the standard error of the mean.

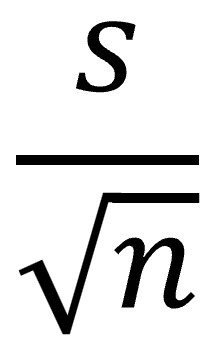

Here’s the neat part: to calculate the standard error of the mean, we don’t need to collect tons of samples, find the mean of each one, and then compute their standard deviation. We can estimate it directly from our sample by dividing the sample’s standard deviation by the square root of the sample size:

If you take a closer look at that formula, you’ll see that the larger the sample size, the smaller the standard error and the more precise our estimate of the mean becomes.

This makes intuitive sense: a mean based on 10 patients can swing wildly from one sample to the next, but a mean based on 500 patients is much more stable, less vulnerable to outliers or random variation. That’s why the standard error is essentially a way of measuring how much uncertainty is baked into the average we’re using to estimate something.

The standard error matters because it lets us build confidence intervals, run significance tests, and even determine whether a difference between groups could just be due to chance. And while it’s often confused with the standard deviation (which tells us how much individual data points vary), the standard error doesn’t speak about individuals: it tells us how confident we can be in the average we’ve calculated, when using it to make an inference.

We’re leaving…

And now it’s time to wrap things up, so I’ll try to leave on a slightly more optimistic note than the one we started with.

We’ve seen how the central limit theorem teaches us that, in the midst of the noise and chaos of individual data, there’s always the possibility of finding order. That our estimates, however uncertain they may be, can rest on solid principles that help us understand not just the values themselves, but also how much trust we can place in them.

It’s clear that quantifying the uncertainty of an estimate isn’t just a fancy statistical add-on; it’s essential to avoid misinterpretations that could lead to rushed conclusions or straight-up bad decisions. And the compass that guides us along this path is none other than the standard error of the mean, the tool we’ll use to build our beloved confidence intervals. But that’s another story…